First published: 28/05/2024

Last updated: 05/10/2025

From 9,817 Jews in the land of historic Palestine in the Ottoman census of 1881, the number increased through mass immigration to 554,000 in 1948, the year of Israel’s creation. Even so, the Palestinian population remained in the majority and did not accept this modern invasion, so six regional wars followed; two Palestinian popular uprisings (intifadas); and six Israeli wars over Gaza (the sixth being the one that began on 8 October 2023 and will be dealt with elsewhere on this website). The death toll between 1900 and September 2023 has been at least 79,338 Arab-Palestinians and 12,159 Jewish-Israelis.

The chronology presented below contains only a limited number of footnotes and/or hyperlinks. All the sources of information consulted are included in a pdf (only available in Spanish-Castilian) that you will find in the Spanish- Castilian version (castellano) of this entry on this website.

Please consult for bibliography: (1) on Palestine and Palestinians: http://www.mideastweb.org/palbib.htm; (2) on Zionism: http://www.mideastweb.org/zionbib.htm; and (3) on the history of Israel and Palestine since 1880: http://www.mideastweb.org/isrzionbib.htm.

1. Three controversial issues from the distant past

There are three controversial issues from the distant past: (1) the location of historical Israel (Palestine or Asir); (2) the expulsion of Jews from historical Palestine (reality or myth); and (3) purity and superiority of the Jewish race (myth or reality). This first part of the chronology will include an exposition of the two main theories underlying these three controversies.

1.1. Historical Israel is located in Asir

(1.A) The traditional Jewish account holds that the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh [acronym for the 39 books it contains, the 5 of the Law (Torah), the 22 of the Prophets (Nevim) and the 13 of the Writings (Ketuvim)], also known in the Christian worlds as ‘The Old Testament’, took place in the territory of historic Palestine, where the Kingdoms of Israel and Judea would be located. To access the traditional Jewish account, countless sources can be consulted: I suggest Oliver Leaman’s book ‘Judaism’ or the page on ancient Israel on Wikipedia.

However, there is no archaeological or toponymic evidence that the Hebrew Bible took place in the territory of historic Palestine. No inscriptions found in Palestine by archaeologists refer either to biblical Jerusalem or to any other place in the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh.

Likewise, although the Tanakh records that the chosen people went to Egypt, none of the ancient Egyptian inscriptions record this fact, which has always been very strange to historiography, given the known meticulousness of Egyptian historiography.

(1.B) Against this traditional account is the research of the Lebanese historian Kamal Salibi, who argues that the history of the Kingdom of Israel as recorded in the Hebrew Bible took place from the 11th to the 6th century BCE in what is now the region of Asir and southern Hijaz, in what is now southwestern Saudi Arabia.

Salibi argues this in his book ‘The Bible Came from Arabia’ -book available in Arabic, English and German-, based on a careful analysis of the toponymy (place names) of that area.

The core of Salibi’s etymological-historical explanation is based on the fact that the Hebrew Bible, which must have existed in its present written form probably before the 5th century BC, has been consistently mistranslated. Why? Because ancient Hebrew, also called Biblical Hebrew, ceased to be a living language in common use around the 6th or 5th century BCE; Jews switched to speaking the languages of the area (in fact, modern Hebrew was created by Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, a revolutionary from Tsarist Russia who emigrated in 1881 to the territory of historic Palestine).

Since the Hebrew Bible was only written (as with all Semitic languages 1 including Arabic and Aramaic) with its consonants, not its vowels; and the Hebrew Bible was not vocalised by Jewish scholars until the late Middle Ages [estimated to be between the 6th and 10th century CE], the scholars who vocalised and interpreted that Bible had not spoken Hebrew as a living language for centuries and vocalised it from their tradition, but perhaps without sufficient actual linguistic knowledge. Hence the merit of Salibi’s research, namely to attempt to reread the Hebrew Bible, with special emphasis on the thousands of place names it contains, on the basis of the phonology and morphology of one of the two other Semitic languages that have survived uninterruptedly since antiquity as living languages, namely the Arabic language.

All the place names mentioned in the Hebrew Bible have survived to the present day concentrated in this region of Saudi Arabia, as Salibi demonstrates in his book through detailed etymological and geographical explanations based on catalogues of place names and maps of Saudi Arabia published between 1978 and 1981. Thus, he documents the survival, among many other places, of: Jordan (p. 83 of chapter 7); Judea (pp. 40 and 97); Jerusalem (pp. 110, 117 and 119-122 of chapter 9); Hebron (p. 111); Zion (p. 115); Jezrael (p. 128); or Samaria (p. 128).

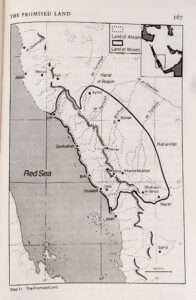

By way of example, the map reproduced below corresponds to the map contained in Chapter 15 of the book, specifically on page 167, which shows what were the territories mentioned in the Hebrew Bible in the part that speaks of Abraham (Genesis 15:18) and Moses (Numbers 34:1-12), the so-called ‘Promised Land’.

As for Egypt, Moses was never in the Egyptian Sinai, but the biblical Mount Horeb (Deuteronomy 1:1) can be identified, from the surviving toponymy (place names) in the area, with the present-day Jabal Hadi in the coastal area of Asir (p. 35 and note 8 on p. 204).

Finally, although it would be very important for archaeological expeditions to be carried out in Asir to confirm the above, the survival of this toponymy in Asir, together with the non-existence in ancient historical records of this toponymy in the territory of historic Palestine, support Salibi’s conclusion that the Hebrew Bible took place in Asir, a conclusion which I share, and which links to the following point in this chronology.

1.2. Emigration of Jews to Palestine, and… expulsion and diaspora?

From the 8th century B.C.E. Jewish emigration from the Asir area to the area of historical Palestine began after the civil war between Israel and Judea, reinforced by the invasion of the Assyrian Sargon II in 721 B.C.E. and the Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar in 586 B.C.E. The Greek historian Herodotus already describes Palestine in ‘The Histories’ in the 5th century B.C.E.

Alexander the Great’s conquests in 330 B.C.E. had put an end to the Persian empire in the area of historic Palestine, and upon Alexander’s death his territories were divided among his generals and Palestine came under the control of the Seleucids.

The Jews of Palestine began a revolt against the Seleucids around 167 B.C.E. and achieved independence around 142 B.C.E., establishing the kingdom of the Hasmoneans.

With the arrival of the Romans in the area in 63 B.C.E., the kingdom of Judea, tributary to Rome, was established in Palestine under Herod the Great (37-4 B.C.E.).

(2.A) Rome destroyed the temple in Jerusalem erected by Herod and forced the expulsion of the Jews from historic Palestine, first from Jerusalem and Judea in 70 C.E., followed by further deportations until 135 C.E., the year in which the Bar Kohba rebellion (also known as the Third Jewish-Roman War or Third Jewish Revolt) took palce. It would appear that as of that year Jews would have been expelled from that land, a land to which, precisely in 135 CE, the Roman emperor Hadrian gave the name Palestine. From then on, the Jews settled throughout the world, first mainly in the Arab world, North Africa and Europe, giving rise to the Jewish Diaspora, i.e. the dispersion of the Jewish people and their descendants.

(2. B) In contrast to this historical account, historians such as the Israeli Shlomo Sand argue in his book ‘The Invention of the Jewish People’ that ‘the Jewish Diaspora is essentially a modern invention’; he explains that the Jews appeared on the Mediterranean shore and on the European continent through the conversion of the local populations to the Jewish faith, arguing that Judaism was, at the time, a ‘converting religion’. He argues that conversions were first carried out by Hasmoneans under the influence of Hellenism and continued until Christianity became the dominant religion in the 4th century CE.

(3.A) The expulsion and Diaspora theory is often accompanied by a third element: the purity of the Jewish race and its superiority to all other races as the only race chosen by Yahweh (God).

(3.B) Sand argues that the ancestors of most contemporary Jews most likely came from outside the Land of Israel; that there never was a Jewish ‘nation-race’ with a common origin; and that, just as most early Christians and early Muslims were converts from other faiths, Jews are also descended from converts.

In conclusion, whether or not the total expulsion of the Jews from the territory of historic Palestine in the second century occurred; whether or not that diaspora was generated from Palestine; and whether or not the Jews are a ‘race-nation’, what is important to be clear about is that events which happenend thousands of years ago cannot be used to justify acts in the 20th or 21st century and that, in the 21st century, no race is superior to any other, all are equal.

After the division of the Roman Empire, the territory of historic Palestine was from the 2nd to the 18th century, first under the domination of the Eastern Roman Empire, then successively under the control of: Arabs (636-1099), who brought Islam with them; Christian Crusaders (1099-1187); Ayyubids (1187-1250); Mamluks (1250-1516); and the Ottoman Empire (1516-1916).

The Jews, on the other hand, were subject to further expulsions from Europe. Thus, what is certain is that Jews: (1) were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula between 1492 and 1498 2, creating the Sephardic Jewish branch that migrated in the 15th century from the Iberian Peninsula to France and the United Kingdom, to North Africa, to the Middle East and to the Balkans; and that (2) in central Europe there was the Ashkenazi Jewish branch that also suffered expulsions. Since these subsequent expulsions are closer in time there are already reliable sources of information about them, but they are no longer directly linked to the land of historical Palestine.

2. From the birth of Zionism to the creation of the State of Israel

2.1. Birth and expansion in the 19th century of Zionism and its aliyot into historic Palestine

The 19th century saw the beginning of two processes:

1. The enunciation of political Zionism by several rabbis in the 19th century and culminated by Teodor Herzel who published in 1896 his book ‘The Jewish State’ and organised and chaired in 1897 in Basel (Switzerland) the First Zionist Congress which created the Zionist Organisation (ZO). The ‘Basel Programme’ stated that: ‘The aim of Zionism is to establish for the Jewish people a publicly and legally secure home in Palestine’ and considered four ‘practical means for this purpose:

- The promotion of Jewish settlements of farmers, artisans, merchants in Palestine.

- The federation of all Jews into local or general groups, in accordance with the laws of the different countries.

- The strengthening of Jewish sentiment and consciousness.

- Preparatory measures for the securing of government subsidies necessary for the realisation of Zionist aims.”

This Congress was opposed by two of the three branches of Ashkenazi Judaism, Reform and Orthodox. Successive Zionist Congresses created the support network to finance the purchase of land in Palestine. This Zionism was opposed to the prevailing idea up to that time, which was that of assimilationism, i.e. that the Jews of the world should integrate and live in peace in their host countries.

2. At the same time, the migration of Jews to the territory of historic Palestine, known as aliyah or its plural aliyot, began in 1881: The Jewish population in historic Palestine grew at the rate indicated in the following table:

|

YEAR |

JEWS | % JEWS

/ TOTAL |

PALESTINIAN ARABS | % PALESTINIANS / TOTAL | TOTAL |

| (1) 1881 | 9,817 | 2,3% | 413,729 | 97,12% | 425,966 |

| (2) 1922 | 83,694 | 11% | 657,560 | 86,84% | 757,182 |

| (3) 1945 | 554,000 | 31,4% | 1,179,000 | 66,8% | 1,765,000 |

Source: Self made with data from those three census 3

Although the Ottoman census of 1881 divided historic Palestine into three regions, in Europe the area was still known as Palestine. Thus, for example, the United Kingdom established the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1865.

One of the founding slogans of Zionism was ‘a land without a people for a people without a land’, which was categorically contradicted in 1891 by the Jew Ahad Ha’am 4.

2.2. Occupation of the territory of historic Palestine by the UK and British Mandate since 1922

During the First World War (WWI, 1914-1918), in May 1916 to be precise, France and the United Kingdom (UK) had concluded the Sykes-Picot Secret Agreement by which the two countries divided up the Middle East and, in application of which, the UK occupied the region of Palestine from the beginning of 1917.

In parallel, the British had reached secret agreements in 1915 with Husayn ibn Ali, the Sherif of Mecca, and Ibn Saud (Darin Agreement) to launch an Arab revolt against the Ottoman Empire, which began on 5 June 1916 and ultimately served British interests.

A third avenue for UK action was to negotiate with the Zionists. The then British Foreign Secretary Balfour signed on 2 November 1917 a brief letter to Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild, leader of the UK Zionist Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland, a text that took several months of negotiations between the British and Zionists, and which is known as the Balfour Declaration. That brief text, which was published in the British press on 9 November, contains three paragraphs: (1) an initial salutatory paragraph; (2) a central one in which the UK favours the creation of a ‘Jewish national home’ in the territory of historic Palestine; and (3) a third, concluding paragraph.

The Zionists, in turn, negotiated with part of the Arabs (Faisal-Weizmann Agreement of 1919) that they would recognise a Jewish state in Palestine.

The League of Nations [the international predecessor of the United Nations (UN) that existed between 1919 and 1946] formally recognised the British Mandate for Palestine on 24 July 1922. Thanks to the British Mandate, the Jewish community of Palestine – the Yichouv – became a quasi-state. As provided for in Article 4 of the Mandate, in 1922 the UK recognised the Zionist Organisation as its official interlocutor in all economic, social and other matters that might affect the establishment of the Jewish national home, a role that was taken over by the Jewish Agency in 1929.

On 23 October 1922, the British published a Census of Palestine. Of the 757,182 inhabitants of this multi-ethnic region, according to its Table I, the vast majority were Muslims (590,890, 78.03% of the total), followed by Jews (83,694, 11%), Christians (73,024, 9.64%) and other minorities (9,574, 1.33%, of whom 7,028 were Druze and the rest were Samaritans, Bahais, Metawilehs (Shia), Hindus and Shijs). Table XXI of the Census shows Arabic as the mother tongue of 657,560 people (86.84%), Hebrew of 80,396, English of 3,098, Armenian of 2,970, Indian of 2,061, Yiddish of 1,946, German of 1,871, Greek of 1,315, Russian of 877 or Spanish of 357.

The mainly Arab population of historic Palestine, which for seventy years – from 1850 to 1920 – had welcomed the Jews without violence, objected from the early 1920s to this growing immigration, which implied the occupation of their land by the Jews and their subjection to them (since the British awarded the main tenders for the Mandate’s public works, starting with electrification, to the Jews), This led to successive and increasingly violent revolts by the local Arab population, which between 1922 and 1936 resulted in 198 Jewish deaths and 193 Arab deaths 5 (the most violent being the Hebron Massacre of 1929 in which 67 Jews were killed). Even so, in those years the Ayan (the intelligentsia of notable Arabs) mediated on countless occasions, saving many lives.

After each revolt, the British conducted commissions of enquiry and produced White Papers. In the 1922 White Paper, then Colonial Minister Winston Churchill made it clear that the provisions of the Mandate did not mean, as Zionist representatives believed, that ‘the whole of Palestine should be made a Jewish national home, but that such a home should be founded in Palestine’ 6.

The UK opened the door to the legalisation of Jewish migratory waves to the territory, and the growth of the Jewish population in the territory of historic Palestine was, from then on and through successive waves of immigration, exponential and unstoppable. “Between 1917 and 1948, the Jewish share of the population rose from 12% to 34%…. From 1932 to 1939, 247,000 people arrived, 30,000 per year, four times more than after the end of WWI, …benefiting from the agreement called Haavara reached by the Zionist Organisation with Berlin in 1933”.

Palestinian leaders submitted a Memorandum in November 1935 calling for ‘the immediate suspension of immigration, a ban on the sale of land to foreigners and a democratic government with a parliament of proportional representation’. In the face of Jewish refusal (to avoid being in the minority) and British inaction, a general Arab strike was launched in Palestine in April 1936, including a boycott of Jewish products. The Arab High Committee was set up and demonstrations were organised, which became increasingly violent.

Following these clashes, the Peel Commission issued the first Partition Plan for Palestine on 7 July 1937. The UK obtained a no to this Plan from both the dominant Jewish party at the time (the Zionist-Socialist Mapai party, the party that controlled the political scene until 1968) and the Palestinians.

The British authorities banned the Arab High Committee in September 1937 and, from that autumn onwards, Palestinian protests were revived and lasted until 1939. The UK mobilised 50,000 troops to crush the Arab uprising with the help of 20,000 Jewish policemen and 15,000 members of the Hagana (the Yishuv’s defensive force), to which were added several thousand militants of the Irgun (the Zionist extreme right). The Arab revolt of 1936-39 resulted in 5,000 Palestinian, 500 Jewish and 262 British deaths.

In this context, the UK produced a new White Paper, the MacDonald White Paper of 17 May 1939, which rejected the idea of dividing the Mandate into two states and advocated a single independent Palestine governed jointly by Arabs and Jews, with the former retaining their demographic majority. In implementation of this plan, the UK banned the establishment of the Jewish state and capped Jewish migration to Palestine at 75,000 over the next 5 years. The Zionist movement rejected the Plan outright 7, and the Palestinians did not accept it either.

The Zionist movement meeting at the Biltmore Conference in New York in 1942 denied the legal or moral validity of the Plan and, going beyond the vague idea of a ‘national home’, advocated the creation of a Jewish Commonwealth in Palestine. Zionism came to be controlled by its most radical wing.

From 1944 onwards, the Zionist insurgency against the British intensified, with terrorist acts such as that committed by the Zionist paramilitary group Lehi, which assassinated British-born Walter Guinness in November. In an attempt to control the situation, the British carried out Operation Agatha on 29 June 1946, which included the arrest of much of the Jewish leadership of the Yishuv, the so-called ‘Black Sabbath’. In reaction, the Irgun carried out the 22 July 1946 bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem which killed 91 people, 28 of them British. British public opinion, which had lost 150 servicemen in Palestine in two years, exerted pressure, accelerating the UK’s exit from Palestine.

During World War II, Nazi Germany and its allies killed in an institutionalised manner (known as the Holocaust or, in Hebrew, Shoa) between 11 and 17 million people:

- Between five and six million were Jewish men and women, although the precise figure is difficult to know with complete accuracy, that is the most widely accepted international estimate.

- Some 220,000 Roma in Europe, out of the approximately one million Roma living in Europe at the time.

- The rest of those murdered belonged to different groups: millions of Polish communists; other sectors of the political left; Soviet prisoners of war; homosexuals; and the physically and mentally disabled.

The Holocaust had a major impact on the collective consciousness of the West[note]Corbí Murguí, H: ‘El Impacto del Holocausto en la Conciencia Colectiva de Occidente’ in: Judaism. Contribuciones y Presencia en el Mundo Contemporáneo, Cuadernos de la Escuela Diplomática, nº 51, 2014: https://www.exteriores.gob.es/es/Ministerio/EscuelaDiplomatica/Documents/documentosBiblioteca/CUADERNOS/51.pdf[/nota], and was instrumental in the international acceptance of the Zionist cause and the acceptance of Jewish colonisation of historic Palestine, despite the fact that it was Nazi Germany that perpetrated the Holocaust, not the Palestinian Arab population of Palestine.

2.3. UNGA Resolution 181

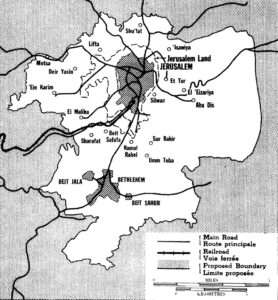

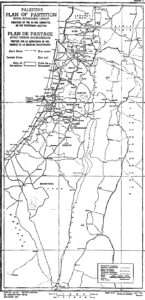

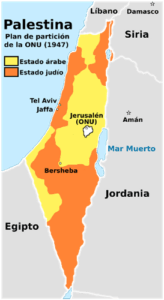

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) adopted Resolution 181 (II) on 29 November 1947 with 33 votes in favour; 13 against; and 10 abstentions. This resolution entitled ‘Future Government of Palestine’ contained a Plan for the Partition of Palestine with Economic Union into two sovereign and independent states: an Arab state and a Jewish state; and the city of Jerusalem to be placed under UN administration. Despite the fact that the Arab population at the time was more than twice the size of the Jewish population, the plan allocated 52% of the territory to the Israeli people, while the Palestinian people assumed the remaining 46%, with the added difficulty of not enjoying continuity in their territory. This led the Palestinians to reject the plan.

The resolution was accompanied by Annex A, which included the partition map of Palestine reproduced below in both its original version and a modern colour version of the same partition; and by Annex B with the map of Jerusalem’s borders, also reproduced below.

Twelve days before the adoption of Resolution 181, whose chief Jewish negotiator with the British had been Golda Meir, Meir had reached an agreement with King Abdullah of Jordan to partition Palestine, as both were against a Palestinian state within the borders of Resolution 181.

2.4. Israel’s unilateral declaration

Following the passing of UNGA Resolution 181 II, in January 1948 Golda Meir travelled to the US to raise funds, as the Zionist leadership believed that war was inevitable. Meir raised donations in the US to buy $50 million worth of arms for the Haganah, arms that were instrumental in reinforcing the Zionist military strategy set out in Plan Dalet of 10 March 1948; the first operation was Nachshon in April 1948 to lift the blockade of Jerusalem being carried out by troops led by Abd Al-Qadir Al Husseini, nephew of the Mufti of Jerusalem. On 2 April, the Haganah seized the Palestinian village of Al-Qastal (the first Arab village to be seized and demolished by the Zionists), and the Arab countries refused military support to Al Husseini to recapture it. In those weeks, the Deir Yassin massacre was also carried out, during which Zionist paramilitaries from Irgun and Lehi killed 120 Palestinian civilians (the first massacre of many).

Finally, the unilateral Declaration of Independence of the State of Israel took place on 14 May 1948. However, international law experts argue that Israel was established without legitimacy over the territory 8. Despite this, and largely in reaction to the Nazi Holocaust, Israel was eventually admitted to the UN in 1949.

3. The six Arab-Israeli wars

The first Arab-Israeli war (1948-1949) 9 was launched the day after the Declaration of Independence by five Arab states opposed to the unilateral declaration (Egypt, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan and Syria) and involved the expulsion of 750,000 Palestinians by Israeli troops, the so-called Nakba or catastrophe; the systematic destruction of 531 Palestinian villages and 11 Palestinian cities which were emptied of their inhabitants; hundreds of thousands of hectares of land confiscated; and the annexation by Israel of 26% of the land allocated to the Palestinian Arabs by Resolution 181 (II), occupying 77% of the territory of the Mandate. The West Bank came under Jordanian control and Gaza under Egyptian control. There were 13,000 Palestinian civilian casualties; between 10,000 and 15,000 Arab combat deaths and 6,373 Israeli casualties (4,000 soldiers and 2,373 civilians).

In contrast to the traditional Israeli view that the Palestinians had fled at the urging of Arab armies, the new Israeli historians 10, after studying the material that was partially declassified in the 1980s (although Morris requested wider declassification which was denied by the Israeli Supreme Court in 1986), argue that the Palestinian population was driven out of their villages and their villages razed and wiped off the map by Israeli troops.

On 17 September 1948, Sweden’s Folke Bernadotte, the first mediator in the history of the UN, was assassinated in Jerusalem by Yeshua Cohen, an Israeli Zionist terrorist belonging to Lehi, in an assassination planned by four men, one of them Yitzak Yezernitsky, the future prime minister of Israel, Yitzhak Shamir, just the day after Bernadotte had finished drafting his proposal for a division into two states with a special status for Jerusalem; and had delivered a report on the destruction of villages.

On 11 December 1948, the UNGA adopted Resolution 194 (III), which enshrines the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and to be compensated for the losses they have suffered.

In 1949, the UN made a first attempt at a peace conference, the Lausanne Conference, which did not succeed.

The Arab League established the ‘All Palestine Government’ on 22 September, which was effective only in Gaza, under Egyptian control, while Jordan annexed the West Bank at the Jericho Conference on 1 December.

Following Israel’s attack on Egyptian troops stationed in Gaza, Egyptian President Nasser decreed the closure of the Strait of Tiran to ships and planes coming from or bound for Israel. For its part, Israel with the support of the UK and France launched a joint attack on Egypt in what was called the Suez War of 1956, by which Israel occupied the Sinai Peninsula. It was a war of choice 11 designed to achieve national objectives. There were between 1,650 and 3,000 Arab combat deaths, 172 Israeli, 16 British and 10 French.

The Franco-Israeli rapprochement also brought about the development of Israeli nuclear energy, which materialised in 1958 with the creation of the Dimona nuclear power plant. Since then, Israel’s nuclear programme has remained outside international legality, as both international organisations and Israeli experts have criticised.

In this context, Palestinians began to organise themselves into different associations to resist. The most important was the PLO (Palestine Liberation Organisation), founded in May 1964 in Jerusalem with the support of the Arab League and at the behest of Egyptian President Nasser, as a unified Palestinian organisation.

In 1967 Egypt mobilised soldiers in the Sinai, which again endangered the departure of Israeli ships to the Red Sea. On 5 June 1967, in the face of Egypt’s refusal to unblock the Gulf of Aqaba, Israel bombed Egyptian aircraft in the Sinai Peninsula, thus starting the Six-Day War. In the six days of the war, Israel conquered the Gaza Strip, the West Bank, East Jerusalem, the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights (Syria). The war resulted in a second wave of 300,000-400,000 Palestinian refugees, the Naksa, almost a third of whom became refugees for the second time. Most went into exile in Lebanon, Jordan, Syria and the Persian Gulf states. There were between 11,510 and 18,214 Arab and 777 Israeli combat deaths.

Arab countries meeting in Khartoum (Sudan) in September 1967 agreed on a Resolution whose Article 3 contained the doctrine of the 3 No’s: no negotiations, no recognition and no peace with Israel.

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) unanimously adopted Resolution 242 on 22 November 1967, which enshrines the principle of ‘peace for territory’, i.e. that Israel will achieve peace when it returns the territory it militarily occupied by force during the Six-Day War.

Between 1967 and 1973, a so-called ‘war of attrition’ was waged. Israel maintained its military occupation of all the territories conquered during 1967, subjecting the Palestinian population to martial law and encouraging Jewish settlement in the occupied territories, in clear violation of the Fourth Geneva Convention, article 49 of which prohibits the transfer of civilians from the occupying power to the occupied territory. As for East Jerusalem, Israel annexed this part of the city at the conclusion of the 1967 war and began demolishing Palestinian neighbourhoods and building Jewish neighbourhoods in their place.

In September 1970, the ‘Black September’ took place in Jordan, a low-intensity war between the PLO and the Hussein regime of Jordan, which is considered to be the beginning of the expulsion of the PLO from Jordan.

In parallel, during these years, the PLO intensified attacks against Israeli interests inside and outside Israel, such as: the Palestinian hijacking of the Sabena airliner (8/05/1972); Japanese Red Army massacre, led by pro-Palestinian Japanese Republican Fusako Shigenobu, at Lod airport, with 26 Israeli dead (30/05/1972); and Munich massacre, with 11 Israeli dead, eleven athletes participating in the Olympic Games in Munich, Germany (5 and 6/09/1972).

The then Prime Minister Golda Meir refused to negotiate the release of Palestinian prisoners in exchange for the Israeli athletes, who unfortunately ended up dead, and ordered Israeli intelligence services to target all Palestinian ringleaders with the ‘Wrath of God’ operation.

Between 1970 and 1973, Golda Meir’s foreign policy allowed Russian and Soviet emigration of Jews from the former Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) to Israel via Austria, estimated at 200,000 people. On 28/09/1973 seven of these Jewish emigrants were taken hostage in Austria by Syrian Arabs demanding the closure of the Jewish Transit Centre; and safe passage to an Arab country. In Vienna, then Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir tried to convince the then Austrian Chancellor, Bruno Kreisky, who was also Jewish, not to give in to ‘terrorist blackmail’, but Kreisky managed to rise above Israeli pressure and save seven lives, unlike in Munich the previous year.

On 6 October 1973, the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, Yom Kippur War, Ramadan War or October War started, an armed conflict between Israel and the Arab countries of Egypt and Syria, who launched their attack to recapture the territories Israel had occupied since the 1967 war. The Egyptian army crossed the Suez Canal, quickly overcoming Israeli defences. At the same time, Syrian forces advanced into the Golan Heights. Having recaptured the Sinai Peninsula, Egyptian President Sadat decided to halt the Egyptian front, allowing Israel to concentrate all its forces on the northern front, invaded Syria and threatened the capital, Damascus; at the same time, Israel advanced in the Sinai counteroffensive, pushing the Egyptians back beyond their borders and across the Suez Canal. There were between 8,000 and 18,500 Arab combat deaths and between 2,521 and 2,800 Israeli casualties.

The Arab countries, faced with this reality, decided to launch an economic war and embargoed the oil of the countries that were helping Israel, while at the same time reducing sales in an attempt to push up prices. Its effect, which went down in history as the 1973 oil crisis, was to destabilise the international economy, putting pressure on the US and USSR to reach an agreement through the UN that resulted in UNSC resolution 338 of 22 October 1973, which allowed a ceasefire to be reached on 25 November, and recommends the start of negotiations with a view to ‘bringing about a just and lasting peace in the Middle East’. Egypt began to move away from Soviet theses and towards the US, while Syria maintained its positions linked to the USSR.

On 21 December 1973, the Geneva Conference organised by the UN to broker peace was held, but it too failed.

On 11 November 1974, Yasser Arafat, as leader of the PLO, addressed the UNGA in New York in a speech explaining the historical origins of the conflict and reaching out to negotiate a just peace.

The heightened sense of vulnerability caused by the Egyptian-Syrian offensive prompted Israel to begin unilateral peace negotiations with Egypt, and on 17 September 1978, Egyptian President Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Begin signed the Camp David Peace Accord in the presence of US President Jimmy Carter. This agreement marked Israel’s first peace treaty with an Arab country and the implementation for the first time in Israel’s history of the land-for-peace doctrine set out in UNSC Resolution 242. Israel had to return territory conquered in 1967, including the dismantling of several settlements established north of the Sinai Peninsula. Egypt was perceived as a traitor to the Arab cause; its President Sadat was assassinated in 1981; and the country was suspended from the Arab League until its readmission in 1989.

After Black September 1970, thousands of Palestinian guerrillas were expelled from Jordan, and the PLO decided to set up bases in Lebanon. In 1978 the UN deployed an interposition force (UNIFIL) in the area, but tensions continued.

In June 1982 Israel invaded Lebanon in ‘Operation Peace for Galilee’, relying on the Christian-Maronites. Under US mediation, Palestinian fighters were evacuated and the PLO leadership was established in Tunis. The assassination of the Christian-Maronite President Gemayel by a Syrian agent provoked the entry of the Israeli-backed Lebanese Phalanges into the Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Chatila, leading to the ‘Shabra and Shatila Massacre’, which caused some 6,000 Palestinian deaths and can be seen as part of the long Lebanese civil war (1975-1990).

Israel bombed the PLO headquarters in Tunis in October 1985, which was severely criticised by the UN (UNSC Res. 573).

4. The first Palestinian intifada and the hope for peace with the 1993 Oslo and 1995 Taba Accords

December 1987 saw the start of what came to be called the First Intifada, a Palestinian popular movement in the Gaza Strip, the West Bank and East Jerusalem against the Israeli occupying forces with the aim of ending the occupation, although the direct trigger was the killing of four workers in Jabalia (Gaza) when their vehicle was rammed by an Israeli military truck. At that time the cleric Ahmed Yassin created Hamas, a Sunni Islamist movement affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, which Israel encouraged in its early days to fuel rivalry with the PLO led by Yasser Arafat.

The First Intifada lasted until 1993 and resulted in an estimated 1,374 Palestinian and 93 Israeli deaths.

On 15 November 1988, the unilateral Palestinian Declaration of Independence, which had previously been approved by the Palestinian National Council (PNC), the legislative body of the PLO, was proclaimed in Algiers. It encouraged recognition of Palestine by several UN states.

Between 30 October and 1 November 1991, the Madrid Peace Conference brought together delegations from Israel, Syria, Lebanon, Egypt and a Jordanian-Palestinian delegation, sponsored by the US and the USSR, followed by ten rounds of negotiations in Washington. The rounds of talks did not come to fruition: (1) in their first leg, when the chief Israeli negotiator was Shamir, ‘because his ideological commitment to Greater Israel left little room for compromise’; and (2) in their second leg, when the US team changed after the elections, as Clinton again unilaterally supported Israeli theses and was no longer able to act as an honest broker. 12

In parallel, direct secret peace talks took place between Israel and the PLO, under Norwegian auspices, leading to the Oslo Accords, a first between Israel and the PLO on 13/09/1993, signed in Washington; and a second, initialled in Taba on 24/09/1995 and signed in Washington on 28/09/1995. These agreements established the Palestinian National Authority (PNA), which would be responsible for managing various public policies in Gaza and the West Bank, which was divided into areas A, B and C; Israel retained foreign policy, defence and borders; and five years were given to negotiate a permanent agreement that would address issues such as the status of Jerusalem, Palestinian refugees and Israeli settlements.

Even so, and according to the then Prime Minister Peres at the Council of Ministers on 13 August 1995, the Taba agreement allowed Israel to ‘retain in Israeli hands 73% of Palestinian land in the West Bank; 97% of its security; and 80% of its water resources’. 13

On 26 October 1994 Israel and Jordan signed a Peace Agreement that normalised relations and ended territorial disputes.

However, just as peace seemed to begin to penetrate – and its architects won the 1994 Nobel Peace Prize – there was, first, in February 1994, the Hebron massacre in which an Israeli-American killed 29 Palestinians, and in the aftermath of which Palestinian suicide bombings began; and, on 4 November 1995, the assassination of then Israeli Labour Prime Minister Issac Rabin by an Israeli religious Zionist extremist/terrorist. 14

5. The Radicalisation of Israeli Politics, the Second Intifada and the Shadow of Peace

In 1996, in Israel, the Likud party (Zionist right) came to power in Israel under Benjamin Netanyahu, who again pushed for the creation and expansion of Jewish settlements in Palestinian territory.

At the same time, in 1996, the first Palestinian presidential and parliamentary elections were held: Arafat won the former with 88% of the vote and his Fatah party won 55 of the 88 seats in the latter.

In 1999, Labour won again in Israel with Ehud Barak and peace negotiations resumed: the US-sponsored Camp David negotiations in July 2000 and the January 2001 negotiations between Israel and the PNA in Taba (Egypt) to address the outstanding issues, although no agreement was reached due to the proximity of parliamentary elections in Israel.

On 29 September 2000, then Likud candidate Ariel Sharon visited Jerusalem’s Al-Aqsa Mosque, Islam’s third holiest site, in a defiant gesture, which, coupled with enormous frustration at the lack of tangible progress for the Palestinian cause, sparked the Second Intifada. It lasted until 2005 and resulted in an estimated 3,368 Palestinian and 1,008 Israeli deaths.

UNSC Resolution 1397 of 12 March 2002 supports Palestine as a state living side by side with Israel ‘with recognised and secure borders’; it calls for an end to violence and a return to peace negotiations.

The Arab Peace Initiative adopted by the Arab League Summit in Beirut on 27 March 2002 offers to lay the foundations for peace.

The US, the EU, Russia and the UN set up the so-called Madrid Quartet in Madrid in April 2002, with offices in East Jerusalem, to try to address the spiralling violence and put the peace process back on track. The Quartet presented on 30 April 2003 a three-phase Roadmap for Peace, including the creation of a sovereign and independent Palestinian state by 2005, which was endorsed by Israel, the PNA and the US, and also by the UNSC through Resolution 1515 of 19/11/2003.

6. Preparing the endgame for Gaza and the end of the dream of a Palestinian state

Sharon took office as Israeli prime minister in March 2001 and, during his mandate, on the one hand, he started the construction of the wall that separates Israel from the West Bank and that has been declared contrary to international law and illegal by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on 9/07/2004 15 and, on the other hand, he carried out in August 2005 it carried out a unilateral withdrawal from Gaza and dismantled 21 Israeli settlements in Gaza, although Israel has continued to control 6 of Gaza’s 7 border crossings (the remaining one, Rafah, being theoretically controlled by Egypt, although in practice Israel exercises ultimate control), as well as its air and sea space and its public services (water, electricity, telecommunications, etc.).

In January 2006, Palestinian elections were held for the second time: Fatah’s Mahmoud Abbas won the presidential elections with 62% of the vote; and Change and Reform (Hamas) won the legislative elections with 72 out of 132 seats. Hamas’ Ismail Haniya was appointed Palestinian prime minister in March 2006. Israel’s reaction was to cut off financial transfers to the PNA and put pressure on the Quartet to put pressure on Abbas, who eventually dissolved Haniya’s Palestinian government in May 2007. Yet, if one reads Haniya’s statements, he does not call for ‘the destruction of Israel’, but for Israel to recognise a Palestinian state and the rights of its people, and considers that as long as the Israeli occupation continues, Palestinian resistance is legitimate. Since 2006 there have been no parliamentary elections in Palestine; the PNA has run the West Bank and Hamas Gaza, after which both Israel and Egypt enacted a blockade of Gaza. All subsequent attempts to reunify Palestinian politicians (2017 Cairo or 2022 Algiers) have failed.

Once Gaza was cleared of Jewish settlers and the Palestinian political class was divided, Israel began to focus its operations in Gaza.

During Operation Cast Lead, Israel began bombing Hamas positions in Gaza, followed by a land, sea and air offensive between 27 December 2008 and 18 January 2009 that killed 1,300 Palestinians and 11 Israelis.

Between 14 and 21 November 2012, Israel launched Operation Pillar of Defence against Gaza, killing 162 Palestinians, including Hamas leader Ahmed Jabari.

From 8 July to 26 August 2014, Israel launched Operation Mighty Cliff over Gaza, killing around 2,200 Palestinians and 73 Israelis.

The Great March of Return in Gaza, which advocated for Palestinian refugees’ right of return, pitted Gazans against Israel between 2018 and 2019 and left some 312 Palestinians dead.

Between 6 and 21 May 2021, a new conflict occured following rocket fire from Gaza in response to the evictions of Palestinian families from Sheikh Jarrah in East Jerusalem and subsequent Israeli attacks resulting in 253 Palestinian and 13 Israeli deaths. Adding the above data, between 2008 and 2021, there were 4,200 Palestinian civilian deaths in Gaza.

As of 7 October 2023, the sixth war in Gaza since the unilateral Israeli withdrawal from the Strip in 2005 is underway. This conflict is addressed in a separate document on this website.

In parallel, Israel regularly carries out, especially in the West Bank and East Jerusalem:

- Restrictions on movement and forced house confinements;

- Demolitions of houses (5,598 between 2006 and September 2023);

- Arbitrary administrative detentions (1,310 in September 2023);

- Security detentions (4,764 in September 2023), all quantified by the Israeli human rights NGO Btselem.

- It also quantifies the number of Palestinians killed by Israel as victims of extrajudicial killings. Thus, the same NGO has quantified the number of Palestinians killed by Israelis, both by official Israeli authorities and settlers, at 10,672 between 2000 and September 2023 (compared to 1,330 Israelis killed by Palestinians).

Moreover, Israel’s violation of the human rights of the Palestinian population has been reported in successive UN reports. 16

For its part, the international community has continued, while allowing Israel’s impunity to continue, to endorse peace proposals that have not come to fruition.

The US-sponsored Annapolis Conference in November 2007 set the end of 2008 as the deadline for a final agreement on all outstanding permanent status issues.

US President Obama attempted to relaunch peace talks by meeting separately with Prime Minister Netanyahu and President Abbas in March 2014, but no progress was made.

UNSC resolution 2334 of 23 December 2016 supports the two-state solution and notes that ‘the establishment of settlements by Israel in the Palestinian territory occupied since 1967, including East Jerusalem, has no legal validity’.

US President Trump supported the signing in 2020 of peace agreements between Israel and several Arab countries, known as the Abraham Accords, including with the United Arab Emirates (UAE) on 13 August; with Bahrain on 15 September; with Sudan on 23 October; and with Morocco on 10 December.

In September 2022 the Independent Commission of Inquiry in the Occupied Territories issued a report describing in detail the situation of the occupation. On 30 December 2022 the UNGA adopted resolution A/77/247, point 18 of which asks the ICJ for an opinion on the legal consequences of the occupation, i.e. on the illegality of the Israeli occupation and the obligation to withdraw. The ICJ is expected to give its opinion in the second half of 2024.

7. Brief historical overview in terms of territory, population and ideology

This ‘Brief Chronology’ provides a series of threads that allow us to summarise what has happened in the land of historic Palestine since the advent of political Zionism in 1900 in terms of:

7.1. Territory

Of the approximately 26,300 km² of historic Palestine, the 1947 Partition Plan allocated 46% to Arabs and 52% to Jews. However, Israel has been increasing its holdings in various ways:

- Land purchases: intense from 1881 until 1948. Even so, in 1948 only 6% of the territory of historic Palestine was in Jewish hands.

- Destruction of 500 Palestinian villages during the Nakba of 1946-49, appropriation of these territories and erasure of Palestinian identity from these places.

- Annexation of territory by successive wars, annexing 26% of Palestinian land in 1948; and exercising an occupying power over the entire Palestinian territory since 1967, an occupation that is illegal.

- Annexation of territory by Zionist settlements on occupied Palestinian land, built since 1967. These settlements and the infrastructures that serve them give Israel and Israeli settlers direct control over 40% of the West Bank and 63% of the West Bank Area C, according to the Israeli human rights NGO Btselem. Israel increased the number of settlers in the West Bank, excluding Jerusalem, from 800 in 1973 to 111,600 in 1993; to 234,000 in 2004; and to 468,300 in 2022; and the number of settlers in East Jerusalem has increased from 124,000 in 1992 to 236,200 in 2021. Despite this continued expansion, the settlements are illegal according to art. 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949 and UNSC Resolution 2234 of 2016, as the EU has also been monitoring and denouncing.

The continued occupation of Palestinian territory by Israel means that the land available to the future Palestinian state is shrinking.

7.2. Population

In terms of population, the following should be highlighted:

- Exponential increase in the Jewish population from 9,817 in 1881 to 6,982,000 in 2021. This sharp increase in the Jewish population has been due to two reasons: (a) on the one hand, the waves of migration encouraged by political Zionism and spurred on by the United Kingdom since its occupation of Palestine in 1917; and (b) on the other hand, the high birth rate of ultra-orthodox Jewish women (Haredi), which is around 4%, bringing Israel’s Haredi population to 750,000 in 2009, up from 1,280,000 in 1881 to 1,280,000 in 2021. 750,000 in 2009, 1,280,000 in 2022 and an estimated two million in 2033.

- The Palestinian Arab population, which in the 1922 British Census of Palestine was 657,560, 86.84% of the total, now stands at 7,478,450, living in Palestine and Israel.

- For any final peace agreement, it is essential to bear in mind the Palestinian population expelled before (250,000) and during (750,000) 1948, and in 1967 (350,000) and their descendants, a population that UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East) estimates at 5.9 million refugees.

- The conflict has had a very high cost in human lives, especially for the Palestinian population. According to my calculations, 79,338 Arab-Palestinians and 12,159 Jewish-Israelis 17 have died between the beginning of the conflict in the early 20th century and September 2023, a total of 91,497 human beings.

7.3. Ideology: Zionism

The ideology that has guided both the creation and development of Israel has been Zionism. Zionism has sought from the outset, as Churchill warned in his 1922 White Paper, the creation of the Jewish state on the entire territory of historic Palestine, i.e. Greater Israel, what I call the ‘ultimate goal of Zionism’.

To articulate this goal, which is incompatible with a Palestinian state, Zionism, both secular and religious, has resorted to violence to derail successive political strategies for statehood:

- Bi-national state strategy advocated by the UK in 1939 with the MacDonald Plan, which secular Zionism opposed from the outset and which led Zionism to resort to terrorism to drive the British out of there (Guinness assassination in 1944 and King David Hotel bombing in 1946).

- The UN strategy for the internationalisation of Jerusalem provoked a new assassination by secular Zionists, that of the first mediator in UN history, the Swede Bernadotte, in 1948, the day after he presented his Plan that included a special status for Jerusalem.

- The two-state strategy (Oslo Accords of 1993 and Taba of 1995) was stopped by a new Zionist assassination, this time a religious one, in 1995, that of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, who had signed them.

Likewise, Zionism has managed to articulate a policy of impunity towards Israel, which in the occupier-occupied binomial holds the position of political, economic, military and informational strength, and which has been supported by elements such as:

- Systematic non-compliance with the international legislation emanating from the United Nations, which requires Israel to put an end to the occupation, dismantle the wall, stop the settlements or respect the human rights of the Palestinian population, for which it has counted on the unconditional political-military overprotection of the USA and its economic support (77 billion dollars between 1948 and 1992, and between 3 and 4 thousand a year since then, that is to say, some 180 billion dollars).

- A self-interested exploitation of the tremendous effect the Holocaust had on the collective conscience of the West to paralyse a significant part of international actors, including within the EU.

- The intentional confusion of criticism of the Jewish race (known as anti-Semitism and equivalent to a type of racism that is punishable in most national legislations) with criticism of Zionism (known as anti-Zionism and equivalent to a criticism of a political ideology and therefore permitted in most national legislations). And on this basis, they succeed in discrediting, cornering and, finally, silencing any criticism. Criticising Israel’s violation of human rights or its unwillingness to contribute to the creation of a sovereign and viable Palestinian state is not anti-Semitism, it is anti-Zionism, and it is legitimate. There are many Jews who are critical of Zionism, Jews who are obviously not anti-Semitic.

- A clever use of the terrorist concept to pin it on the occupied population and its leaders, intentionally forgetting that the Palestinian cause is a cause of pending decolonisation according to the ‘Fourth Committee: Special Political and Decolonisation Committee‘ following the Palestinian question; and that UNGA Resolution 37/43 of 3 December 1982 in its point 2 reaffirms “the legitimacy of the peoples struggle for independence and… liberation… from occupation… by all means at their disposal, including armed struggle’.

- An even more skilful handling of the Zionist lobbies or pressure groups in the world, such as the very powerful American AIPAC; and, through these lobbies, a skilful strategy of positioning itself in political, economic, financial and media power circles at both national and international level. Specifically, and by way of example, in the US, despite the fact that Jews make up only 2% of the population, President Biden’s administration had Jews in many of its key positions, such as Secretary of State (Blinken), Secretary of the Treasury (Yellen), Secretary of the Interior (Mayorkas), Attorney General (Garland), Director of National Intelligence (Haines), White House Chief of Staff (Klain) and Deputy Director of the Central Intelligence Agency (Cohen).

For its part, the Trump administration also has numerous Jews in its ranks, both in its departments and in the White House, the National Security Council, NASA and its embassies around the world. In addition, Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner, continues to exert his pro-Zionist influence and direct matters of utmost importance, such as the ‘Trump Plan for Peace in Gaza’ of 29/09/2025.

Notas a pie de página- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semitic_languages. The Semitic concept was originally a linguistic concept referring to languages that had a common origin (Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, etc.). In the 19th century, this concept came to have a racial meaning and to be identified with the Jewish race: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Semitic_people, hence the term anti-Semite is applied today to the fact of being against Jews, although, strictly speaking, it would be to be against any Semite, including being against Arabs.[↩]

- Jews were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula (the area which in Hebrew was called ‘Sepharad’), specifically and consecutively, in 1492 from Castile and Aragon, 1496 from Portugal and 1498 from Navarre. Those Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula were subsequently given the name Sephardic; they continue to speak Ladino (a variant of Old Castilian); and in 2015 the Spanish House of Commons passed a law granting Spanish citizenship to the direct descendants of the Sephardic Jews expelled between 1492 and 1498. The Jews who were not expelled were forced to convert to Christianity.

However, Jews were not the only ones; Muslims were also expelled from the Christian Iberian Peninsula. Thus, in 1502 all adult Muslims were ordered to be expelled from Castile and in 1527 all Muslims in Aragon were forced to convert (at which point Islam officially ceased to exist in the newborn Spain), but, as this was not enough to eradicate Islam, in 1609 the then King of Spain and Portugal, Philip III, expelled 300,000 Moriscos (Muslims forcibly baptized into Catholicism, but still practicing Islam). There has still been no law in Spain or Portugal recognizing as Spanish and/or Portuguese the direct descendants of the Muslims and/or Moors expelled between 1502 and 1609. Could this be due to a lower lobbying capacity of the Muslim lobby as opposed to the Jewish lobby, “lobbying” being understood as ‘a group or organization dedicated to influencing politicians or public authorities in favor of certain interests? Maybe…[↩]

- Sources:

(1) The Ottoman census of 1881-1882 recorded, in the three districts that at that time made up historic Palestine (Akka, Belka and Kudus), a total population of 425,966 inhabitants, of which Palestinian Arabs would be 413,729 (371,969 Muslims and 41,760 Christians) and 9,817 Jews according to the information available in Kemal Kerpat’s book ‘Ottoman population 1830-1914 demographic and social characteristics’, University of Wisconsin Press, 1985. I have compiled a table with the correspondences between these three Ottoman districts and present-day Palestine and Israel: MAPS COMPLEMENTING THE 1881 OTTOMAN CENSUS. I have also extracted from Kerpat’s book (Table 1.8.A, with Akka and Belka in pages 128 and 129; and Kudus in pages 144 and 145) all the data concerning the population in historic Palestine in 1881 distributed by religion and you can download it here: OTTOMAN GENERAL CENSUS 1881.

(2) For downloading the 1922 British census, click here: https://ia804709.us.archive.org/3/items/PalestineCensus1922/Palestine%20Census%20(1922).pdf. I have made a specific PDF with the main tables, Tables I and XXI (pp. 8 and 59), of the Census which you can find here: 1922 Palestine British Census pags 1-8 & 59

(3) The 1945 British ‘village statistics’ [downloadable at: https://users.cecs.anu.edu.au/~bdm/yabber/census/VillageStatistics1945orig.pdf] contain, on their first page, the population data (for easier reading you can click on this simplified file which I have elaborated: 1945 Village Statistics original-1-3); and in these statistics the British also note that in 1945 the Jewish population owned only 6% of the all the land in Palestine.

In any case, as the parameters are not exactly the same in the three documents the comparison must be made with caution, for example in: (1) they record Jews, Muslims, Christians, Latins, Protestants, etc, i.e. religions; in (2) they record different religions in Table I and languages, the majority being Arabic, in Table XXI; and in (3) they record Jews and Arabs, i.e. mixing religion with race.[↩]

- The Jew Arthur Ginsberg, whose pseudonym was Ahad Ha’am, wrote in 1891, after his first visit to historic Palestine: ‘We are in the habit of believing… that the land there is now entirely desert, arid and uncultivated… but the truth is quite otherwise. Throughout the whole country it is difficult to find arable fields that are not already cultivated.’ https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/ahad-ha-rsquo-am[↩]

- It is very difficult to obtain reliable aggregate data on Arab and Jewish deaths during the British Mandate. See page 26 of Dominique Vidal’s book, Antisionisme=Antisémitisme? Réponse à Emmanuel Macron, Libertalia, 2018 and the Wikipedia page containing partial listings: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_killings_and_massacres_in_Mandatory_Palestine#cite_ref-RAABIC_1-19.[↩]

- https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-196917/ Within this link, go to document nº5 and specifically to its enclosure (enclosure in nº5), to its second paragraph, sixth sentence.[↩]

- The website of the Israel Holocaust Museum states that, after the 1939 White Paper, ‘the Zionists were confronted with a situation that demanded new decisions… the Zionists had to recognize that the alternative to a state in Palestine – the active, even violent option – had been imposed on them…. Now, after May 1939, the ‘revolutionary option’ mentioned by Chaim Arlosoroff in 1932 was at hand….During the 21st Zionist Congress (Geneva, August 1939)…David Ben-Gurion, Chairman of the Jewish Agency proclaimed: “The “White Paper” has created a vacuum in the Mandate. For us, the ‘White Paper’ does not exist in any form, under any condition and under any interpretation… and it is up to us to fill that vacuum, alone… We alone will have to act as if we were the State in Palestine; and we will have to act so until we are and so that we become the State in Palestine“. https://www.yadvashem.org/articles/academic/holocaust-factor-birth.html[↩]

- See the book “El proceso de paz en Palestina” by the professor of public international law at the Autonomous University of Madrid (UAM), Alfonso Iglesias Velasco (UAM editions, 2000, pp. 36-37). For a more detailed analysis of this issue, see another document in this section of the website entitled: “Proposal for a Solution to the Conflict between Israel and Palestine”.[↩]

- These two websites list, respectively, all the Arab-Israeli and Israeli-Palestinian wars from 1948 to the present day: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arab%E2%80%93Israeli_conflict and https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Israeli%E2%80%93Palestinian_conflict.[↩]

- Among these historians and their works, the following can be highlighted: Ilan Pappé with ‘The Ethnic Celansing of Palestine’, Oxford Oneworld, 2006 [https://yplus.ps/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Pappe-Ilan-The-Ethnic-Cleansing-of-Palestine.pdf] and Benny Morris with ‘The Birth of Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited’, Cambbridge University Press, 2004, [http://larryjhs.fastmail.fm.user.fm/The%20Birth%20of%20the%20Palestinian%20Refugee%20Problem%20Revisited.pdf]. An interactive map of the towns and villages from which the Palestinian population was expelled during the Nakba can be found on the following page: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_towns_and_villages_depopulated_during_the_1947%E2%80%931949_Palestine_war. You can also visit other websites such as: https://www.zochrot.org/articles/view/56528/en?iReturn; https://www.palestineremembered.com/index.html.[↩]

- Ein breira: Jewish principle of ‘no alternative’. This principle, which was the basis of the Zionist narrative about Israel’s involvement in successive wars, was broken in 1982 when Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin gave a lecture at the Military Academy on wars of choice and wars of no choice and argued that both the 1956 Sinai War and the 1982 Lebanon War were wars of choice designed to achieve national objectives. https://www.gov.il/en/pages/55-address-by-pm-begin-at-the-national-defense-college-8-august-1982.[↩]

- For Israeli historian Avi Shlaïm’s analysis on Shamir’s reaction and on how and why the US ceased to be an honest broker, see chapter 7 of his 1995 book ‘War and Peace’. The book can be read in English at: https://archive.org/details/warpeaceinmiddle0000shla/mode/1up. For more information on the Oslo Accords, see: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oslo_Accords. For a more detailed analysis of both this peace conference and the agreements that followed see another document in this section of the website entitled: ‘Proposed Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’.[↩]

- When internet did not exist, information had to be verified in different international yearbooks. One of them, and perhaps the most famous, was ‘Keesing’s Record of World Events’, also known simply as ‘Keesing’. In Keesing’s volume 41, number 7/8, dated 25/09/1995, p. 40704, attached here as a pdf, you cand find that statement highlighted in yellow on the third page: 1995 Páginas del Keesing’s Recorld of World Events.[↩]

- ‘Religious Zionism and the Rabin Assassination.’ Tradition: A Journal of Orthodox Jewish Thought, vol. 48, no. 4, 2015, pp. 12-17. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/44821371. There it is explained that Rabin was murdered because his assassin, Yigal Amir, considered him a rodef, a persecutor who endangered Jewish lives, according to the Jewish ‘din rodef’ or Jewish ‘law of the persecutor’ enunciated by Maimonides, which obliges one to save any persecuted person from his persecutor, even if it means killing the persecutor. That is the same principle which Israel applies to its targeted killings inside and outside Israel’s borders, killings that are illegal under international law.[↩]

- The ICJ advisory opinion can be found on the ICJ website: https://www.icj-cij.org/case/131, by clicking on the right-hand column under ‘Advisory opinion’. The gist is in paragraph 163.[↩]

- There are countless documents from the UN, and specifically from its High Commissioner for Human Rights, OHCHR, that deal with this issue; as a ‘sample button’, see: https://www.ohchr.org/en/special-procedures/sr-palestine; https://undocs.org/en/A/73/447; https://undocs.org/es/A/77/356. The issue of Israel’s violation of the human rights of the Palestinian population will be analysed more in depth in another document in this section of the website entitled: ‘Proposed Solution to the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict’.[↩]

- There are no statistics that I am aware of that show the total number of Arab-Palestinians and Jewish-Israelis who have died in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The arithmetic sum of the figures given in this ‘Brief Chronology’ (finding the arithmetic mean where a range was given) gives at least 68,666 Arab-Palestinians and 10,829 Jewish-Israelis who lost their lives in the conflict from 1900 to 1999. All these figures have been extracted from the corresponding websites and/or books whose references can all be found as footnotes in the pdf that accompanies the castellano version of this web entry. If these figures are added to those provided by the NGO B’tselem between 2000 and September 2023, the total number of deaths between 1900 and September 2023 would be 79,338 Arab-Palestinians and 12,159 Jewish-Israelis.[↩]